My Profile

My life as a biologist evolved as a result of acquired adaptations in a series of radically different environments. This all began when I was about seven. Our family of four migrated from the crowded suburbs of San Francisco to a 500-acre ranch near Morgan Hill, California. To me it seemed like the far side of the world. For the first time I couldn't see or even hear any neighbors. To keep me from going completely hog wild, my parents enrolled me in Machado Elementary School (the one-room school is now an historical landmark), requiring daily bus trips with a handful of other kids from neighboring ranches. I suppose the isolation bothered my mom a little -- born and raised on a farm in Iowa, then as a teen, moving to California, she had grown accustomed to the conveniences of civilization. After we settled in at the ranch though, I guess all four of us developed an appreciation of a healthful, self-sustained life style resulting from essentially living off the land. Our meals included fresh eggs, milk, fruits, veggies, beef, pork, venison, duck, quail, chicken and trout. Life wasn't easy on the ranch but it was always spicy and full of surprises. If I had brought any of my toys from our former residence, I don't remember. All around me were new forms of entertainment, such as learning to become a real cowboy. I'm not sure why that seemed to me such an honorable occupation, but it certainly seemed to fit what one teacher diplomatically described as, "an outgoing personality."

Our rustic little two bedroom house overlooked cattle pastures framed by white-washed fences, horse corrals, a hay barn and a chicken coop. All of that was only stone’s throw from the fork in a dirt road leading to a pig pen (a really smelly, muddy one). The other branch of the road led to a creaky wooden gate and cattle guard (a closely-spaced series of rails over the roadway that sometimes got me instead of the cows). Soon, the rutted, uneven road became a track narrowing to a foot path through the woods and into hills. It was a scene from a " happy trails to you" television western. But the only "TV" entertainment at the ranch was the occasional Turkey Vulture circling high above the pig pen.

My dad and I were quickly and thoroughly immersed in the rugged ranch-life. My younger sister had always loved animals and was especially fond of chirping baby chicks, newborn calves and her pet donkey, “Sugarplum.” My mom stayed busy hand-washing clothes, churning butter, preparing meals and tending to minor medical emergencies... cuts, bruises, twisted ankles, mud in the eye, etc. The ranch was a happening place...bulls breaking through fences, horses needing shoes, steers to be dehorned and pigs herded up a chute, pushed one-by-one, squealing into a pool of disinfectant several feet below.. Applied biology in your face. Finally I could proudly wear the cowboy hat I had been given on my sixth birthday! When I learned to ride, I introduced my retired parade horse “Captain” to the trails through the back country of the ranch. My mom packed a lunch in the saddlebag and off we went, Captain—with a sway-back, worn teeth and one functional eye—and me, exploring the coast live oak woodland, creeks and ridge tops, nearly every chance I got, after completing my numerous chores. My regular ranch duties included milking the cow, moving irrigation pipes, repairing fences, and everything within my reach, that my dad, the new ranch foreman, had assigned to me.

Livestock was a novelty to me but it was the wildlife on the ranch that caught my attention. Animals I recall included crayfish, newts, Mallard, Wood Duck (off-limits to hunting), Yellow-billed Magpie (mainland California's only endemic species of bird, I learned many years later), Pacific Rattlesnake and Mule Deer. My first glimpse one morning of a georgeous male Wood Duck poised alertly in a shady pond was breath-taking. And I’ll never forget the day my dad showed me a beautiful, black & white banded California kingsnake coiled and motionless inside the pump shed.

Maybe it was the way the shaft of light illuminated the snake’s glistening scales in the darkened corner, or perhaps my dad’s cautious demeanor (as an old-country Irishman, he thoroughly disliked snakes), I’m not sure, but I was mesmerized. Years later at the university, the ranch days a distant memory, I indulged my fascination with reptiles and enrolled in a field class in Herpetology. I quickly changed my major from art to biology; despite an uncertain future, I knew I was on the right path, as Carlos Castaneda wrote, “the path with a heart.”

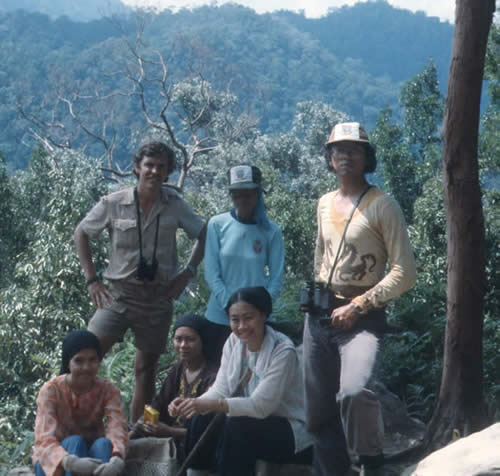

Right path or not, biology was (and still is) a tough major. Working part-time jobs, seven years passed before I earned a bachelor’s degree from California State University Hayward (later renamed Cal State East Bay). Then another year at the same school for a master’s (my thesis was about the reproductive strategies of tropical frogs), three years teaching zoology at the National University of Malaysia as a Peace Corps volunteer, and finally three more years earning a doctorate in zoology at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. At every family get-together I was playfully asked if I would ever finish school and get a real job.

In the mid 1980’s jobs for biologists were downright scarce. Money for teaching and research positions was tight, very tight. The Reagan administration had cut federal programs where biologists might find work; the job market was overflowing with highly qualified biologists, many with a respectable list of publications, who simply could not find work related to their training. And so it was with me. I even considered re-joining the Peace Corps. There was another option, no money involved, but at least it was interesting... avian paleontology in the Hawaiian Islands. Thanks to my major professor at Arkansas, I was invited to join a research team (his daughter, son-in-law, and 2-year-old grandson) from the Natural History Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, and helped them uncover the bones of extinct birds in dust-filled lava tubes of Maui. I spent a week crawling on hands and knees in dark caves, filling bags with dirt, hoisting the bags up a 15-foot ladder, then sifting the material over a doughboy swimming pool in a soggy cow pasture. Bird bones were as rare as paying jobs for biologists. We managed to find the partial remains of an eagle, a flightless goose and two or three honeycreepers—all of which had evidently been driven to extinction before westerners arrived in the Hawaiian Islands.

These findings were remarkable, though my back ached for several days afterward and I still needed a job. Then, early in the summer of 1984, I received an unexpected letter from Rae Yoshida, the Vice President of Academic Affairs at Antelope Valley College. An interview had been scheduled for a full-time teaching position in zoology. Two months later I was on the biology faculty of AVC, where I would be occupying the same office until the fall semester of 2012 when construction of our new Health Sciences building was completed. Again I was reminded that habitats change and life goes on.