VIETNAM

December 9-29, 2017

(See also: Vietnam 2018 Journal and Bird List)

Scouting Trip Report

© Callyn Yorke

Red-shanked Douc (Pygathrix nemaeus) Son Tran Mountain, Da Nang Vietnam 26 December, 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

INTRODUCTION

Shortly after my eighteenth birthday in the summer of 1968, I received written instructions from the US Selective Service to complete a military induction exam near my home in Berkeley, California. I complied, along with about three-hundred other guys my age.

In that same year, American involvement in Vietnam had shifted back into high gear, following a surprise Tet offensive in Saigon. Thousands of young Americans were drafted; some enlisted for patriotic reasons, others for a macho adventure, or simply because they had nothing much going on with their life. It was a nail-biting time for the rest of us. Many college kids (including former President Bill Clinton), strongly opposed the war, living each day on the edge of possible academic annihilation, expecting the next letter from the government to contain official orders telling us where we would be sent for basic training.

US helicopters protecting South Vietnamese solidiers northwest of Saigon in 1965 photo by Horst Faas

![]()

Stripped to our underwear, our motley assemblage of potential inductees was herded from one makeshift room to another. We moved slowly and steadily in separate single-file lines, like ants on a scent trail, through a maze of signed and unsigned stations with uniformed officers barking commands, some sitting, some standing, reading from lists of questions and performing medical exams: Psychological (e.g. Are you a homosexual?), auditory and visual acuity, skin condition, foot and arm rotation, an IQ test, and so on, for several hours.

In one large, gymnasium-sized space, we were marched single file on a tape-line, until a chain of shivering, nearly naked bodies formed an unbroken perimeter of the room. We then were ordered to stop, face the wall, drop our shorts, bend over and spread our butt cheeks. The person next to me laughed and told me to turn around to check out the view. I did. It was unforgettable. About two-hundred exposed hindquarters, of all shapes, sizes and ethnicities - corpulent, bony, white, pink, brown, black; most bald, some comically hairy - obediently mooning their commanders in a grotesque display of theatrical synchronicity. A squad of doctors in white coats hastily examined each of us, stopping occasionally to inquire of certain unlucky gents, something like, "How long have you had this?"

I wasn't raised in a military family, though my dad was a WW II veteran, who, at age 19, served as a medic on the front lines in Belgium. He had very little to say about his wartime experience, except that there was an overwhelming amount of carnage and suffering. My questions about life in the armed forces went largely unanswered until I was faced with the pre-induction physical.

It was with chilling procedural efficiency, probably alien to most of us kids, that the military demonstrated a blatant disregard for personal privacy or dignity. In their view, the task was simply to process the maximum number of able-bodied recruits in the shortest possible time. This was war (though it was never officially declared) and dude, you had better get your act together fast. Thousands of our soldiers, not much older than the ones filling this room, were wounded, dying and dead in Vietnam; replacements were urgently needed.

I passed the induction exam with good marks and was offered a relatively high ranking position with the army counter- intelligence program. I declined the offer, applied for and received, a 2-S college deferment. When that was rescinded in 1969, I received a sufficiently high lottery draft number (mine was above 250, based on a randomization of 365 birthdates), resulting in me being entirely excluded from military service for duration of the war. Less fortunately, a lottery number lower than 100, essentially guaranteed 1-A draft status for everyone who passed the physical. I was raised Catholic, but the Jewish celebration of Passover, took on new meaning. From that time onward, I cringed with everyone else at home, watching the grim evening news, as the bodies piled up in Vietnam, grateful I didn't have to go there. Vietnam looked like hell on Earth.

Legal options for those of us passing the induction exam yet objecting to the war, were few. Former President Bill Clinton took advantage of a United States Rhodes Scholar award, together with his political connections in the government. Traveling back and forth between the US and Oxford, England for his studies, Clinton skillfully (and legally) avoided military service in Vietnam.

The US Peace Corps was another option for avoiding military service, but a four-year college degree was a minimum requirement. I was still a few years from earning degrees in biological science. When I was finished with graduate school, the Vietnam War had been over for two years. I ended up serving three years in Malaysia (1977-80) as a Peace Corps Volunteer.

However, fall-out from the Vietnam War wasn't far away. Floatillas of desperate Vietnamese boat people drifted southward in the South China Sea and into Malaysian waters. On the morning of April 10, 1978, while conducting a zoological survey on Pulau Tenggol (a small island about 27 km east of Kuala Dungun), I held my binocular on an image of a listing wooden boat overloaded with perhaps fifty people. A tattered canvas sail had the letters 'SOS' marked on it. Most of the people on the boat were wearing rags and obviously in bad shape. They were trapped on a sinking boat, unable to land on Malaysian soil due to strict immigration regulations. Nothing could be done for them until the government sent out official rescue ships. Tragically, many Vietnamese boat people perished due to attacks from pirates, drownings, sickness, starvation, dehydration and exposure. The lucky ones were eventually resettled in Canada, the United States and Europe.

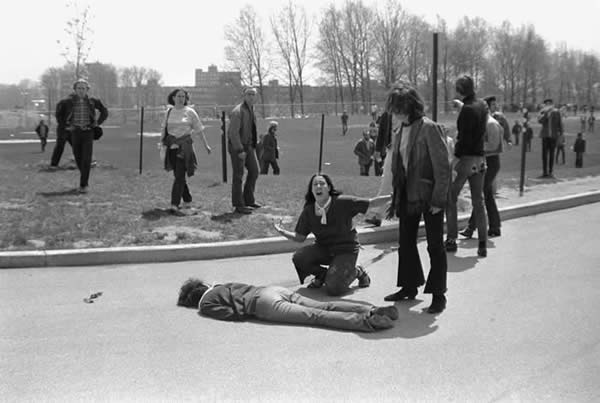

The war pressed on through the Nixon administration, while increasing numbers of Americans (including some Vietnam veterans) participated in anti-war rallies and demonstrations. The most publicized of those events occurred on May 4, 1970 at Kent State University, Ohio. In what appeared on the televised news as an inexcusable use of deadly force, National Guardsmen opened fire on unarmed students, killing four of them and wounding nine others. This was probably the turning point for many Americans at home, sparking widespread outrage and resentment toward our nation's leaders. In effect, although initially assisting the South Vietnamese government with honorable intentions, our nation had been pulled into a terminal vortex of military commitment.

Kent State University, Ohio May 4, 1970

Regrettably, Americans suffered from a fundamental misunderstanding of Vietnamese language, politics and regional history. In essence, our leaders believed an overwhelming military force could quickly pound a small nation of rice farmers into submission. They quite mistakenly underestimated the will and tenacity of the Vietnamese people to liberate themselves once and for all from foreign occupation.

Imagine if at the outset of the American Civil War, the Southern Confederacy begged the Japanese Imperial Army to rescue them, because the Mexicans, Canadians and British were pedalling weapons, ammunition, petrol and anti-slavery propaganda to the Northern Union army. This unlikely scenario is vaguely equivalent to what actually happened in Vietnam. It was a lost cause from the start.

A few days before JFK was assassinated on November 22, 1963 (but thankfully, after establishing the US Peace Corps), his administration had begun plans to pull our troops out of Vietnam. But JFK's successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, saw things differently. Johnson, more focused on domestic than international issues, apparently let the military convince him and nearly everyone else in the White House, that Vietnam was a winable war. Five more years passed without much hope for a resolution. Visibly fatigued by declining health and bad press regarding his role in the Vietnam War, the scrappy old Texan maintained the course until leaving office in January, 1969. The Vietnam hot potato then landed in the lap of Richard Nixon.

The political situation went from bad to worse for the Nixon administration. Most disturbingly, throughout the war, our government provided no credible explanation for the indiscriminate slaughter of Vietnamese women and children by our troops. They sidestepped the issue, implying it was simply wartime collateral damage, deferring to official investigations of specific incidents, such as the My Lai massacre on March 16, 1968. Recent reviews of declassified military documents indicated that such atrocities were not uncommon, e.g. in the densely populated Mekong Delta. Meanwhile, many Americans, educated by a combination of televised news and returning Vietnam veterans, were no longer fooled by optimistic reports coming from the White House. Eventually, it was an overwhelming opposition to the war by the American public, including a few of our own, well publicized civilian casualites, that persuaded the Nixon administration to step up efforts seeking a diplomatic solution to the conflict. The conceptual model Nixon proposed in a televised speech on November 3, 1969, was labeled, "Vietnamization." His plan, scarcely original, and smacking of political appeasement, was to let Vietnam solve its own problems, with minimal assistance from the US.

At least the White House now sounded reasonable and willing to change course. Then it was discovered that in March, 1969, Nixon had ordered secret bombing raids in Cambodia, ostensibly an act of war on a sovereign nation. Our Vietnam military campaign was like an old boat spouting too many new leaks. When peace talks collapsed with Hanoi in late 1972, Nixon resumed heavy bombings of North Vietnam. So much for Vietnamization. The new catch phrase might have been, "Vietnamization or Vaporization."

The North Vietnamese leaders, aware of US rhetoric and of a growing American resentment toward the war, were determined to reunify their country at all costs. They quickly adapted to our superior technology, learning to disarm hundreds of silently dropped, motion-detection bombs, and use decoy trucks and bonfires to mislead infrared scanners on US helicopters and planes, which then flew directly over concealed NVA anti-aircraft gun traps. The NVA rebuilt roads and trails each night following American bombing raids, insuring an uninterrupted flow of Chinese and Russian weapons, ammunition, fuel and supplies, southward along an ever-changing network of roads, known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Dozens of other adaptive measures were learned from trial and error in the field, often at great cost to life and limb for the NVA soldiers involved.

Perhaps most cleverly, the North Vietnamese Army, initially vexed by instantaneous aerial assaults when their vehicle engines started up in remote forest camps, found and disabled our secretly installed listening devices, then relocated and reactivated those devices next to our command posts. It was diabolically effective. The result, like a nasty practical joke, caused the US to bomb its own installations. Embarrassed by the mistake, the US claimed the Viet Cong had infiltrated top levels of military intelligence. Not quite. What they exploited was our military's lack of intelligence. The North Vietnamese were simply observant enough to learn how to use our own technology against us (for a revealing description of the various counter-strategies used by the North Vietnamese Army, see: Dang Phong's historical compilation of first-hand accounts from NVA soldiers and officers, Five Ho Chi Minh Trails, The Gioi Publ. VN, 457 pp. 2016, sec. ed. English trans. ISBN: 978-604-77-0493-4).

Predictably, at least in hindsight, the relentless and undeterred North Vietnamese Army achieved their goal on April 30, 1975. Yet victory came at a horribly high cost. War casualty estimates vary widely (sometimes by an order of magnitude), but the following statistics and conclusions are most commonly cited for the period of 1965-1975: 800,000 NVA and South Vietnamese soldiers killed; 0.5 million civilian deaths (including 84,000 children); at least 1 million people left homeless and 1.1 million Vietnamese ultimately seeking refuge in other countries; 0.5 million hectares of forest destroyed by defoliants; ubiquitous bomb-crater landscapes, undetermined amounts of unexploded ordnance, and a crippled economy.

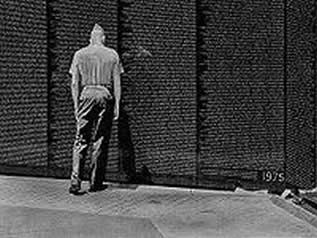

The US armed forces suffered about 58,000 fatalities, most were under 25 years of age. Some of them were doubtless among the pre-inductees with me at the physical exam in 1968. Almost everyone I knew in those days had a friend or family member in the war; a few of my former classmates enlisted or were drafted. The US soldiers who perished in the Vietnam War are now immortalized by the Washington D.C. memorial. It was the most devastating war of my lifetime, and not one that could easily be forgotten by anyone who lived through it.

Vietnam Veterans War Memorial Washington D.C.

VIETNAM JOURNAL

Fast-forward forty-two years. The scene in Vietnam is, happily, quite different from the war ravaged landscapes and piles of corpses that had accumulated by 1975. Indeed, what I found everywhere I went, was an incredibly friendly, welcoming Vietnamese people, anxious to show off their scenically splendid country, the new setting for a frantic pace of modernization. The Vietnamese people have little time for remorse. They are far too busy striving to improve their lives through education, new job opportunities in technology and tourist industries, and living up to their national reputation for determination to succeed, whatever the cost. These people are truly unstoppable. On many levels Vietnam is resilient, dynamic, unique and endlessly fascinating.

The author and Duyen ('Gin') Vu Trong, my birding guide and former North Vietnamese Army soldier, Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

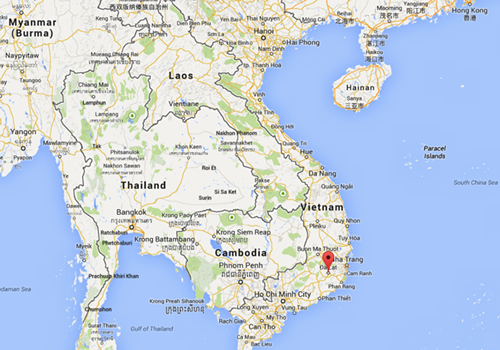

Aside from Vietnam War history, which was ubiquitous, taking the form of monuments, museums, rusty old American military vehicles and planes, unexploded ordnance and ecological scars from defoliants, I found a wealth of bird life and natural history in Vietnam to keep me occupied during a three-week visit. My Vietnam tour began in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), with a brief overnight stay, and a one-hour flight to DaLat early the following morning.

Xuan-Huong Lake, viewed from the Ngoc Phat Hotel, DaLat Vietnam 11 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

DaLat

(December 10-13; 19-20, 2017)

DaLat, in the Lam Dong province of South Vietnam, was established as a mountain retreat for French colonists by the early 20th century. DaLat highlanders enjoy a cool, bracing climate and a blended Franco-Vietnamese culture, with many fine old colonial buildings and some excellent Vietnamese restaurants featuring creative cuisines. Fortunately, in an extraordinary gesture of historical recognition, both sides during the war agreed to preserve DaLat, despite military training camps known to be operating in the area.

Considering the many upscale neighborhoods of DaLat, it was relatively inexpensive to stay there. A four-star hotel overlooking picturesque Xuan-Huong Lake, cost about $50 per night. Taxis are abundant, along with swarms of motorbikes, and can be hired for about $1 per 2.5 km. The only downside was being a pedestrian. No traffic lights or protected crosswalks -- one of the world's great adrenaline-pumping travel experiences, instantly demanding supreme faith in a higher power. Running blind-folded across the 405 freeway in Los Angeles might be safer than crossing a street in DaLat.

The first afternoon of my arrival in DaLat, I became trapped on the wrong side of a busy avenue and had to hail a cab in order to return to my hotel three blocks away. The cab driver laughed and refused to take my money. Later I learned that Vietnam has a relatively high traffic fatality rate (mostly due to motorbike accidents), though significantly lower than that of Thailand. Sightseers, daydreamers, jet-lagged pedestrians, beware.

Lang Biang Mountain, DaLat Vietnam 11 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

The hotel management, learning of my Ornithological interests, arranged for a driver to take me to some natural areas in DaLat. Initially we traveled by a brand new Toyota 4WD SUV with tinted windows and black leather interior. I imagined myself a visiting dignitary being chauffeured around for engagements of international significance. Those musings were short-lived.

All of our subsequent field trips from the hotel were on a used, 60 cc motorbike, which in low gear, had extreme difficulty when burdened with two full-grown riders going up steep hills. We must have looked like a couple of circus bears on a bicycle. If there was a flat road anywhere in DaLat, we never found it. Sometimes, we had to dismount and walk the bike up a hill. It had been years since I had been on a motorcycle. And in those days, I was the driver. Now I was a helpless passenger in a mountain community notorious for a lack of traffic control. I was petrified and maintained a permanent death-grip on the rear seat bar. At the end of each jaunt, my hands were chaffed, crimped and nearly useless for holding a binocular. Apparently, the hotel intended to save money on fuel costs, since they were charging me the same fee (about $20 for a half-day of exploration) regardless of the type of vehicle.

My young driver, Nicki, knew the DaLat area well, but birding was entirely new to him. Nicki guessed where the best birding spots might be and most of the time he was right on. It was a learning experience for both of us.

Nicki and I exploring the outskirts of DaLat, Vietnam 12 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

The first place Nicki and I went was Lang Biang Mountain, where a number of interesting highland bird species are known to occur. But when we arrived, a park official explained that we could not drive the hotel's Toyota 4WD to the top of the mountain. Rather, we must rent one of their jeeps for $500,000 Vietnamese Dong ($22 US). Instead of doing that, we opted to independently walk the road and trails up the mountain.

If there is one attribute most Vietnamese business people seem to possess, it is a deep resentment of other Vietnamese trying to scam their customers. Usually, they jealously reserve that privilege for themselves. Nicki, however, was the exception. He faithfully and enthusiastically provided my daily transportation and local geography lessons (in English), without once asking for additional financial compensation. I was happy to give him a substantial tip when I checked out of the hotel a few days later (tipping is appreciated though rarely expected in Vietnam).

The moderately strenuous mountain hike on Lang Biang was fairly rewarding for bird life. Almost immediately upon leaving the park entrance, on a side trail, a mixed species flock of birds, including a couple of lifers for me, Gray-capped Woodpecker and Black Bulbul, appeared in the mid to lower levels of the pines (Black Bulbul, a gregarious species, turned out to be quite common in wooded second-growth areas around DaLat). Although we made it only part way up the mountain, never reaching the summit (2,170 m), most of the bird life appeared in a sparse understory (scrub oak and scattered shrubs bordering a small coffee plantation), at the 1,670 m level in elevation. Unfortunately, the pine forests here and elsewhere in the DaLat region have been planted as monoculture, which does not support nearly as many bird species as the original rain forests the pines have replaced, e.g. Suoi Tia Forest (see below).

Gray-capped pygmy woodpecker (Yungipicus cannicapillus) Lang Biang Mt. Danang VN 11 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Black Bulbul (Hypsipetes leucocephalus) Tuyen Lam Lake, DaLat Vietnam

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

In fact, it was fairly difficult finding any stands of rain forest within about a 20 km radius of DaLat. The best birding was around the edge of a reservoir outside of town (Tuyen Lam Lake), and along an unsigned secondary road ("Three Little Pigs Road") through a patch of hillside rainforest, known locally as Suoi Tia. The latter area, with steep-sided hills and largely inacessible, supported the best representation of upland rain forest in the DaLat area. Waves of birds in mixed species flocks were at the forest roadside (earlier a family of wild pigs crossed this road, hence the coined name given above). Most of the flocks moved on before Nicki and I could dismount from the motorbike and follow them with a binocular. Unfortunately, our time was limited in those potentially productive birding locations and only a dozen or so species were added to my trip list. The open water of all reservoirs in the DaLat area was largely devoid of visible life, except for a few isolated shoreline patches of tall sedges and shrubs, where bird life was concentrated.

Tuyen Lam Lake, DaLat Vietnam 12 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Suoi Tia Forest, Three Little Pigs Road, DaLat Vietnam 13 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

One bright sunny morning, Nicki and I visited the Truc Lam Monastery, located on a hill near Tuyen Lam Lake. We got there fairly early, before most of the tour buses. On the edges of the exquisitely manicured gardens and temple architecture, we found that by simply waiting quietly in one spot, birds would begin to appear. Within about thirty minutes of our arrival, we had observed at least ten species of bird, some new for my trip list. These included, Green-billed Malkoa, Banded-Bay Cuckoo and Plaintive Cuckoo - the latter gleaning a caterpillar from the ground a few feet in front of us (photo).

Truc Lam Monastery DaLat Vietnam 12 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Plaintive Cuckoo (Cacomantis merulinus) Truc Lam, DaLat Vietnam 12 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

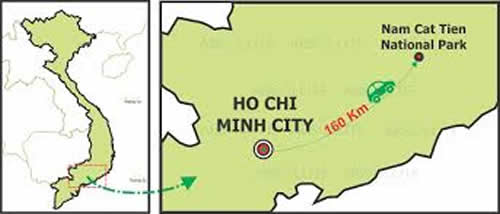

Nam Cat Tien National Park

(December 14-18, 2017)

The scene of repeated aerial spraying of defoliants (Agent Orange) during the war, Cat Tien survived a devastating and largely undocumented biodiversity crisis, dubbed "Ecocide." Fortunately, the rugged western half park was largely spared from the defoliant assault, leaving much of it ecologically intact and serving as a refugia of biodiversity. Given enough time, i.e. 40 years, the remainder of the park could be recolonized and gradually regain ecological functionality and stability.

Nowadays, Cat Tien contains one of the largest tracts (72,000 hectares) of viable lowland rain forest in Vietnam. Indeed, Cat Tien National Park was designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 2001. It is one of the best places in Vietnam to observe relatively secretive forest birds such as partridges, pheasants and pittas. Rare and endangered primates, e.g. Black-shanked Douc and Golden-cheeked Gibbon, also live there. Cat Tien is a high priority for visiting birders and other nature enthusiasts.

Ferry station entrance Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam 14 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

I chose a relatively expensive lodging option within the park, Forest Floor Lodge (FFL), located about 1 km north of park headquarters. There were some inexpensive hotels outside the park, but few options I knew of within the park, which is separated by a river from the adjacent village. A ferry is required to access the park and fees are collected for each entry.

Lodging within the park avoided daily transport inconveniences and allowed for nighttime walks in the forest. I made two nighttime walks from FFL, one solo and the other with a lodge biologist and hotel guest, both walks northward on the main road. Together, the two walks produced a Pygmy Slow Loris (Nycticebus pygmaeus) as well as Palm Civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus) and Muntjak Deer (Muntiacus munjak).

Nighttime flash photography can be challenging due to focusing issues and potential damage to the highly sensitive retinas of nocturnal animals. A FFL biologist, James Holman, assisted me by improvising a red plastic filter for my camera flash unit, and held it in place while I photographed a surprisingly quick-moving, Slow Loris. The results were two identifiable, though rather poor quality photos. Note the prominent yellow eyeshine of the loris, which from 50 m away, was like a pair of small headlights in the forest subcanopy.

Pygmy Slow Loris (Nycticebus pygmaeus) Cat Tien NP Vietnam 17 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Accomodations at Forest Floor Lodge were clean, comfortable and well-maintained. The lodge setting, next to a section of river rapids, was as convenieint as it was picturesque. Guests were treated to close-up views of birds and other wildlife from the dining area. The lodge restaurant featured a reasonably varied menu for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Best of all, the owners (Mia and Roy) and some of their staff were biologists and well versed in local natural history. One young chap in particular, James Holman, who was working on his Ph.D. thesis involving dragon flies, was quite knowledgeable and helpful, particularly when it came to arranging for guides, locating interesting birds, primates, and navigation within the park. The only downside to the Forest Floor Lodge was the cost: about US $1,500 pp for a five-night stay, including part-time guide services.

Forest Floor Lodge main dining area, Cat Tien NP Vietnam 14 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Forest Floor Lodge accomodations (Room 4a) Cat Tien NP Vietnam 14 Dec 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Tokay Gecko (Gekko gecko) about 25 cm Forest Floor Lodge Cat Tien NP Vietnam 14 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Dong Nai River, viewed from the Forest Floor Lodge Cat Tien National Park Vietnam 17 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Old growth secondary forest, Cat Tien NP Vietnam 15 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Birding Cat Tien was a bit slow at first. Birds were everywhere skittish, most likely due to poaching, a common problem throughout Vietnam. Shortly after my arrival, I hired a bird guide, Vu Trong Duyen "Gin," who was a former NVA solidier. Gin and I walked many kilometers together through the rain forest over the next few days, finding some interesting birds, and occasionally stopping for brief but poignant discussions about the war.

Gin and I on the Crocodile Lake Trail, Cat Tien NP Vietnam 16 December 2017

Gin, who said he was a little younger than me, was understandibly reticent about sharing details of his experience in the American war. I didn't press the topic, but listened intently to everything he was quietly saying in his broken English-Vietnamese accent. The content of most of our conversations I have kept to myself, honoring those soldiers who, like Gin, fought bravely in the war. What is truly remarkable, is that Gin and I, once mortal enemies due to our opposing governments, could now stroll together as companions, enjoying natural wonders in the same Vietnamese forests where a great deal of wartime violence had occurred during our more youthful years.

One of the war scars in Cat Tien, was the preponderance of impenetrable bamboo thickets. Whereas some habitat heterogeneity resulted from the invasive bamboo in natural tree-fall areas, it seemed to dominate too many areas of the park. Later, I learned that the widespread use of defoliants in Cat Tien, an NVA stronghold during the war, had encouraged the establishment of large tracts of bamboo, which have persisted for more than forty years. Just how this invasive plant has changed the ecology and diversity of the park is yet unclear. Some species, e.g. bulbuls and flycatchers, seem to thrive in it, while others, e.g. pheasants and hornbills, avoid it.

Gin showed me a relatively new and popular bird photography blind hidden in the forest behind the park headquarters. I spent three separate, 2-3 hour sessions there, mostly alone but occasionally visited by other birders and chatty tour groups, attempting to capture images of a few of the park's elusive bird species, such as Germain's Peacock Pheasant and Bar-bellied Pitta (those two species were found only on the Crocodile Lake Trail). A small clearing in front of the blind was used as a bait station -- someone scattered seeds there early each morning to attract birds. It was certainly an effective, though controversial practice, also done in parts of Thailand. About six bird species (Scaly-breasted Partridge, Blue-rumped Pitta, Siberian Blue Robin, White-rumped Shama, Tickell's Blue Flycatcher and Abbott's Babbler) were fairly regular visitors to the feeding station. The early morning and late afternoon light was dim in the shady forest, leaving only two photographic options to me -- a high ISO setting or a flash. The former turned out to be the best choice, since the birds were generally frightened away by flash photography.

The author using the Cat Tien bird photography blind 15 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Green-legged (Scaly-breasted) Partridge (Arborophila chloropus) Cat Tien NP Vietnam 17 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Blue-rumped Pitta (Pitta soror) immature male Cat Tien NP Vietnam 17 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Siberian Blue Robin (Luscinia cyanae) male Cat Tien NP Vietnam 17 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

White-rumped Shama (Copsychus malabaricus) male Cat Tien NP Vietnam 15 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

According to Gin, the dry season (December-January) is the best time to visit Cat Tien. This isn't so much due to relatively rainless days and dry trails, he said, as it is to the reduced activity of mosquitoes and leeches.

Yet, despite the complete lack of rain during my five-day visit, I was repeatedly and mercilessly attacked by tiny, rather harmless-looking leeches. Seldom more than an inch in length, these determined little annelid slinkies, steadily climb end over end onto a fully clothed person, homing in on the closest available patch of skin, whether that be an ankle or neck. They are not too picky either. If a sweaty groin area is convenient, no problem. They will be sucking away there until so bloated with blood, that the sheer weight of the meal causes them to lose their grip and fall into a bloody little lump, squirming with delightful satiation in your underwear.

Normally, when visting the tropics, I wear tall rubber boots to avoid pesky critters such as leeches, ants and venomnous snakes. For some reason, this time I chose to rely on my water-resistent, light weight, outrageously expensive, The North Face brand boots. Big mistake. Even with my pant legs tucked in my socks and snugly buried inside the top half of my boots, the legendary Cat Tien leeches found bare skin on my lower legs, ankles and feet. By using their anticoagulant - anaesthetic salivations, two or three managed to extract more than their fair share of my blood on a daily basis. Several weeks later the bite wounds remained itchy and slow to heal (photo). Its the jungle gift that keeps on giving.

Leech bites on the Crocodile Trail, Cat Tien NP Vietnam 16 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

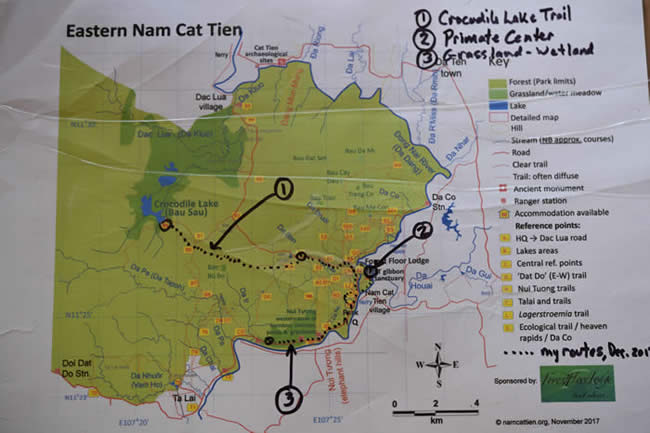

In addition to the second-growth around the lodge and park headquarters, there were other areas particular interest to me. 1) The Crocodile Lake Trail to the west, 2) The Primate Rescue and Rehabilitation Center near the park headquarters, and 3) a large grassland-wetland on the main road in the southeast. All three of these areas contained distictive ecology and wildlife, and yielded many new species for my trip list.

Map of Eastern Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam ----- showing my survey routes Dec. 2017

© 2017 Forest Floor Lodge

Gin led the Crocodile Lake Trail expedition. We set off from the Forest Floor Lodge in a pick- up truck and were dropped off at the trail head on the main road, about an hour before it opened to the public (0900 hrs.). In the interim, we birded the roadside second-growth and forest edge, which was quite productive for barbets, broadbills, bulbuls and flycatchers. Notable finds were: Blue-eared Barbet, Lineated Barbet, Black and Red Broadbill, Ashy Minivet, Black-hooded Oriole, Bronzed Drongo, Pin-striped Tit-Babbler, Blue-winged Leafbird, Asian Fairy Bluebird, Black-headed Bulbul, Streak-eared Bulbul and Little Spiderhunter.

The two-hour hike to Crocodile Lake was pleasant, though disappointing for birding and photography. Birds and primates were audible but skittish; many remaining high in the canopy, keeping out of sight. Gin used a recorder to play back the vocalizations of several relatively secretive forest birds, e.g. Siamese Fireback, Germain's Peacock-Pheasant and Bar-bellied Pitta. Those birds were both heard and seen, but only briefly as they scampered away on the shady forest floor. Primates, including Silvered Langur, Black-shanked Douc and Golden-cheeked Gibbon, likewise were vocal but shy and retiring, never affording more than a glimpse as they moved through the canopy.

Most impressive on this trail were stands of very large, buttressed trees, representing surviving remnants of primary rain forest. Equally interesting was the large lake at the trail's terminus, next to a park ranger station. From the elevated deck of the two-tiered wooden building, we leisurely ate our lunch and observed numerous waterbirds around the lake. Most of those were new for my trip list, including, Lesser Whistling Duck, Cotton Pygmy Goose, Osprey, Purple Heron, Painted Stork, Pheasant-tailed and Bronze-winged Jacana. A rare Siamese Crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis) surfaced near the shoreline.

Crocodile Lake, Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam 16 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

This was unquestionably a worthwhile day-trek in Cat Tien. Not surprisingly, by noon time, the popular trail was crowded with visitors, almost to the point of needing a passing lane.

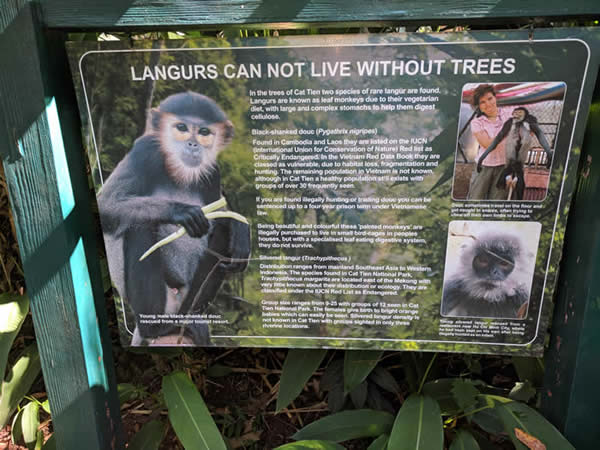

Another popular excursion in the park was to the Dao Tien Endangered Primate Species Center, located on a small tributary near the park entrance. The center, established in 2008, is essentially a 57- hectare island, consisting of old growth secondary forest, clearings, enclosures, a few small buildings and a gift shop. Staff and volunteers are involved with the rescue, rehabilitation and release of principally four primate species, Golden-cheeked Gibbon, Black-shanked Douc, Silver Langur and Pygmy Slow Loris. Rehabilitated animals are released into the more remote sections of Cat Tien NP, with a remarkable 90% success rate.

Hannah's introduction to the Dao Tien Primate Center Cat Tien NP Vietnam 18 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Myself and about ten European tourists took short boat ride from the dock at park headquarters to the primate center. We were given a comprehensive and very informative tour by Hannah, one of the center's staff, ending 1.5 hrs. later (0900-1030 hrs.). A concluding presentation was made in the gift shop, where we also viewed a brief promotional film about the center.

One of many educational signs at Dao Tien Primate Center, Cat Tien NP Vietnam 18 Dec 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Hannah's concluding lecture presentation, Dao Tien Primate Center, Cat Tien NP Vietnam 18 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

During the visit, we were escorted to a viewing platform where a pair of free-ranging Golden-cheeked Gibbons was interacting in the canopy of a distant clump of tall trees. The animals were mostly concealed by the foliage, but occasionally afforded good views (photo).

Golden-cheeked Gibbon (Nomascus gabriellae) Dao Tien Primate Center, Cat Tien NP, Vietnam 18 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Near the end of my visit to Cat Tien, I rented a bicycle from FFL and pedalled a few kilometers south on the main road to a grassland-wetland area. I was joined by two other birders from Canada, David and Elizabeth, who were also visiting Vietnam for the first time. Together we turned up quite a few birds in the grassland area, including some lifers for each of us.

We were told about an observation tower somewhere in the area, and eventually we located it. Since several lower steps were completely gone and floorboards were missing on the upper deck, we chose to bird from the road and walk around the adjacent fields instead. That was a good choice. We spotted several new species for my trip list, including, Red wattled Lapwing, Red-collared Dove, Zebra Dove, Brown-backed Needletail, Blue-bearded Bee-eater, Chestnut-headed Bee-eater, Blue-tailed Bee-eater, Indian Roller, Dollarbird, Common Flameback, Ashy Woodswallow, and White-rumped Munia.

Red-wattled Lapwing (Vanellus indicus) Cat Tien NP Vietnam 18 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Blue-bearded Bee-eater (Nyctyornis athertoni) Cat Tien NP Vietnam 18 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Chestnut-headed Bee-eater (Merops leschenaulti) Cat Tien NP Vietnam 18 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

David and Elizabeth returned ahead of me, while I pedalled back slowly on the bumpy road, stopping frequently to observe birds in the fading afternoon light. I needed to stop often anyway. The seat on my bike was permanently welded at the lowest height setting, and became impossibly uncomfortable, no matter how I shifted my weight. I ended up walking the bike rather bow-legged the last kilometer in the dark.

Out of the darkness, walking toward me, was the figure of a man I recognized -- Gin. He had just finished the day with some other birders. He smiled and asked if the bike a flat tire. We made small talk, shook hands and said our fairwells. I gave him a tip for the mornings he guided me (he humbly accepted the money but said it was too much). We went our separate ways in the night. I wondered if our paths might cross again one day. Gin seemed confident it would be so. Cat Tien certainly has irresistable appeal to biologists. It is one of Vietnam's greatest natural treasures. There is no place quite like it.

Great-eared Nightjar (Eurostopodus macrotis) Forest Floor Lodge Cat Tien NP Vietnam 17 December 2017

© 2017 James Holman

DaNang

(December 21-28, 2017)

A little more than an hour flight north Saigon, DaNang combines stunning coastal scenery with a bustling, rapidly developing, cosmopolitan city. And, dollar for dollar, it is incredibly cheap. I stayed at a four-star, high-rise hotel two blocks from the beach for about $24 per night. The hotel also provided very reasonably priced valet taxi service to and from the airport, along with local excursions, e.g. to Son Tran Mt., Ba Na Mt. and Hoi An.

DaNang, viewed from Son Tran Mt. Vietnam 27 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

DaNang, Vietnam at night from the 36th floor 24 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

An old US radar installation sits atop Son Tran Mountain overlooking the sea. During the war, the mountain was largely off-limits to civilian personnel and consequently remained in a relatively undisturbed, natural state. Almost the entire mountain is covered by forest and second-growth, and is now set aside by the Vietnamese government as a natural preserve, protecting many kinds of birds, together with a small population of the stunningly beautiful Red-shanked Douc. Naturally, I spent as much time on Son Tran Mountain as possible; it was about a 10-minute cab ride from my hotel.

Red-shanked Douc (Pygathrix namaeus) Son Tran Mt. DaNang Vietnam 26 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Coastline of Son Tran Mountain DaNang, Vietnam 27 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

In contrast with the dryness of DaLat and Cat Tien in South Vietnam at this time of year, the monsoon season was just beginning in DaNang when I arrived in late December. Consequently, my time in the field was quite limited, and I was always with an umbrella, often forced to take shelter beneath trees and roof overhangs. There was perhaps only one day during my visit without intermittent rain. Waterproof protection for my camera gear was essential.

Nonetheless, I managed to log several hours of fieldwork on Son Tran Mt., spending much of the time on the grounds of the Linh Ung Monastery. The gardens and especially the edges with encroaching second growth from the adjacent open land, held an amazing diversity of birds. Each of my four separate visits yielded new species for my local bird list.

Linh Ung Monastery, Son Tran Mt. DaNang Vietnam 26 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Son Tran Mountain and Linh Ung Monastery were unquestionably the best birding sites I found in the DaNang area. By the end of my visit, I had added at least thirty new bird species to my trip list, including several lifers.

A notable discovery, made during my last visit to the monastery, was a pair of Peregrine Falcons on a colossal white statue of Buddha. It appeared to be an ideal nesting site but that could not be determined from my vantage point. The birds nonetheless had a commanding view of the entire coastline from the statue, which when illuminated each night by flood lights, could be seen for many kilometers to the south. It would be interesting to know if the falcons nested there despite the nighttime lighting.

Da Thao Le Nguyen in front of Buddha statue at Linh Ung Monastery DaNang Vietnam 23 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) on Buddha statue, Linh Ung Monastery, DaNang Vietnam 27 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Among the many bird sightings made at the monastery and around Son Tran Mountain, were several new ones for my trip list, White-nest Swiftlet, Green-eared Barbet, Red-breasted Flycatcher, Daurian Redstart, Stonechat, Racket-tailed Treepie,Blue Rock Thrush, Brown Shrike, Dark-necked Tailorbird, Stripe-throated Bulbul, Dusky Leaf-Warbler, Chinese Blackbird, Crimson Sunbird, and Japanese White-eye.

Racket-tailed Treepie (Crypsirina temia) Linh Ung Monastery DaNang Vietnam 23 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Daurian Redstart (Phoenicurus auroreus) male Son Tran Mt. DaNang Vietnam 26 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Dark-necked Tailorbird (Orthotomus atrogularis) Son Tran Mt. DaNang Vietnam 26 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Brown Shrike (Lanius cristatus) Son Tran Mt. DaNang Vietnam 26 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Stripe-throated Bulbul (Pycnonotus finlaysoni) Linh Ung DaNang Vietnam 27 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Blue Rock Thrush (Monticola solitarius) female Son Tran Mt. DaNang Vietnam 26 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Crimson Sunbird (Aethopyga siparaja) male Son Tran Mt. DaNang Vietnam 26 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

While staying in DaNang, I visited two other locations, the historical village of Hoi An, about 25 km to the south, and Ba Na Mountain Park, about 20 km to the west. Although both locations were very scenic and/or of historical interest, neither were very productive for birds. However, the flooded paddifields outside of Hoi An had a few egrets, herons and swifts; this area could be a good birding site in the early morning hours when there is relatively light traffic on the main road. The stream and riparian strip at the entrance to Ba Na Park had Intermediate Egret and a White-throated Kingfisher, and that was about all I could see as we sped by.

Hoi An paddifields Vietnam 27 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Hoi An Vietnam 27 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Ba Na Mountain @ 1,670 m elevation viewing west toward DaNang Vietnam 22 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke

Red-shanked Douc (Pygathrix namaeus) Son Tran Mt. DaNang Vietnam 26 December 2017

© 2017 Callyn Yorke